In 2012 after having read a few articles on garment workers and due to very little information available in the public domain, I was compelled to get a deeper understanding of the issue. Soon after that I had met with union leaders who told me that since 2005 nothing much had changed. In fact, production targets had increased, wages were still the same, and very few workers had been promoted, possibly also as a consequence of the fact that the unions are growing at a very slow pace due to aggressive opposition by employers.

In the course of time I started to photograph the garment workers outside of the factory space (mostly in the hours before and after they set off to work) in order to humanize the way they have been represented so far and leave behind, if only temporarily, the discourse of human and working rights. I learnt that there was so much more to their lives besides the fact that they are employed in one of the most exploitative industry sector that is garment production. Their rights, if met, would ensure a better quality of life for them, but their experiences and stories gave me a new understanding of their lives, which I have tried to convey through my pictures.

Bangalore

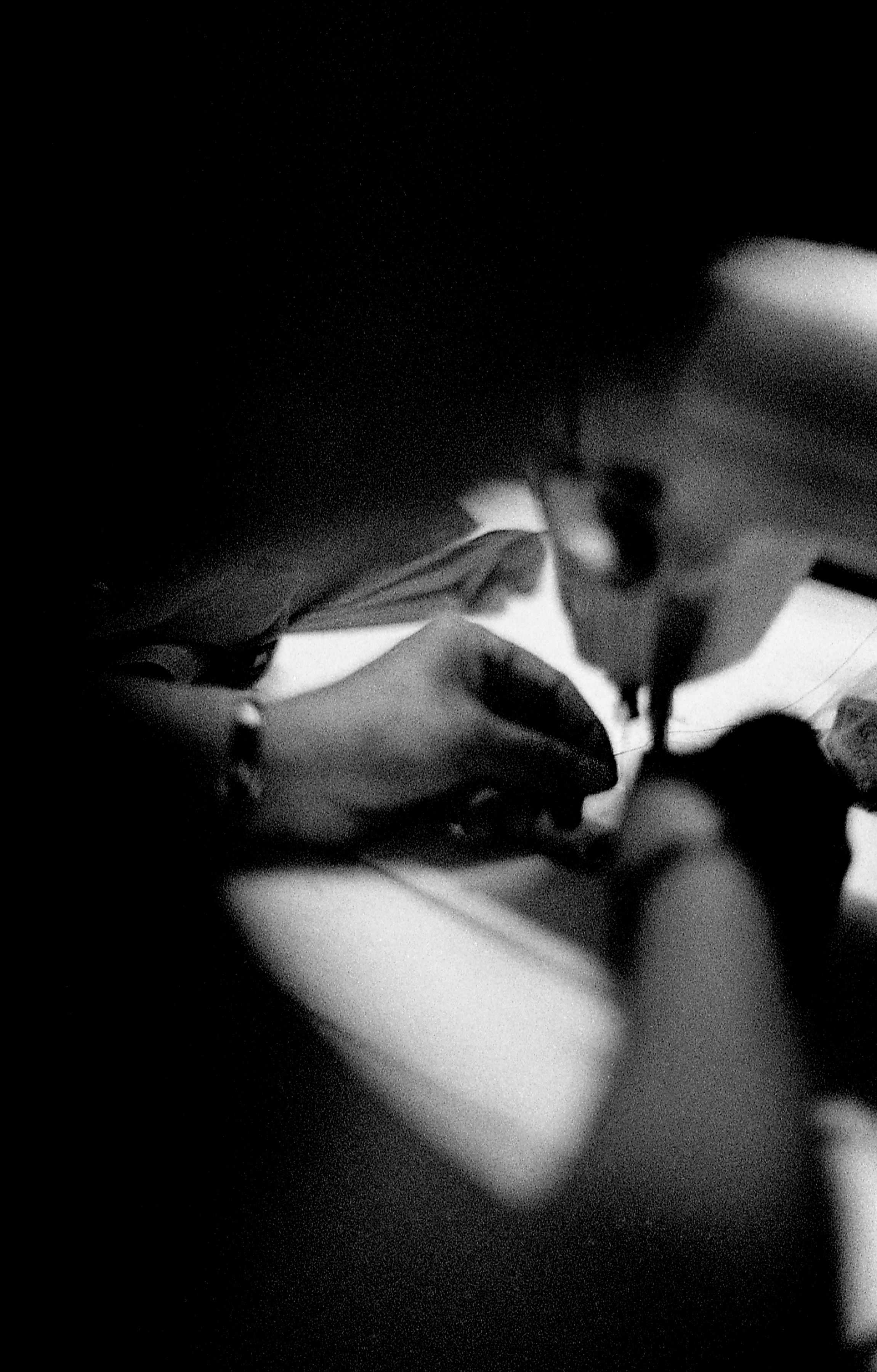

The Bangalore garment industry employs mostly women, who constitute 80 percent of the total workforce. Many of the women are from surrounding villages and commute to work daily by trains, while most of them have moved away from their villages into the city to cut down on both cost and time.

Most of the women here sew men’s clothes, usually trousers and, according to the Indian Textiles and Clothing Exports by the Textile Ministry dated 26 March 2012, Indian textiles industry is pegged at US$ 55 billion at current prices. The textiles industry accounts for 4% of GDP. In Bangalore alone the turnover was over INR 2000 crores in the year 2013.

The minimum wage for a garment worker in Bangalore is INR 4,472 per month, which is said to be 43 percent of what is needed to support a family of four. The present minimum wage figure, developed from the results of the 15th Indian Labour Conference held in 1957, would now amount to somewhere around rupees 15,000 per month.

Asia Floor Wage (AFW), a collective of Asian labour activists who came together to try to create Asia-wide standards in the garment manufacturing industry, demanded a hike in salaries in November 2012, which is yet to be implemented. One of the workers I met told me that a group of them tried to form unions secretly twice, but were issued life threats and its leaders were immediately terminated from the company.

“We are not allowed to take leave for even otherwise strong reasons. If we do, the day we return to the factory, we are made to stand outside. They abuse us by calling us bitches, donkeys and even tell us to go die. Supervisors constantly harass us by calling us names and throwing things like clothes in our faces. I didn’t know the meaning of sexual harassment until I joined a union. I thought it was a norm in factories, so I remained silent for many years without ever once questioning it,” another worker told me.

Most women in Bangalore return home after their hours in the factories to either stitch, work as house helps in the neighbourhood, make flower garlands, papads and various other jobs to boost their low wages they earn at the factory. In the city where inflation has affected everyone, where the prices of milk, oil, vegetables and lentils have climbed up steeply, the low wages paid out to the women working in the garment industry can hardly see them through.

The Bangalore garment industry employs mostly women, who constitute 80 percent of the total workforce.

Many women also work as housekeepers, neighbourhood tailors, domestic help, and flower garland makers, to supplement low wages at garment factories.

Jayamma in front of the Puma showroom on Brigade road, Bangalore. She recognises some of the designs she has stitched.

Many garment workers from surrounding villages commute every day. Kengeri train station serves many coming in from Chennapatna and surrounding areas.

Geeta celebrates Gowri Puja with her daughter at their house in Bangalore.

Most workers have moved away from their villages and into the city to cut down on commuting time and costs.

Sakamma works as a domestic help and cook after her day at a garment factory in the city.

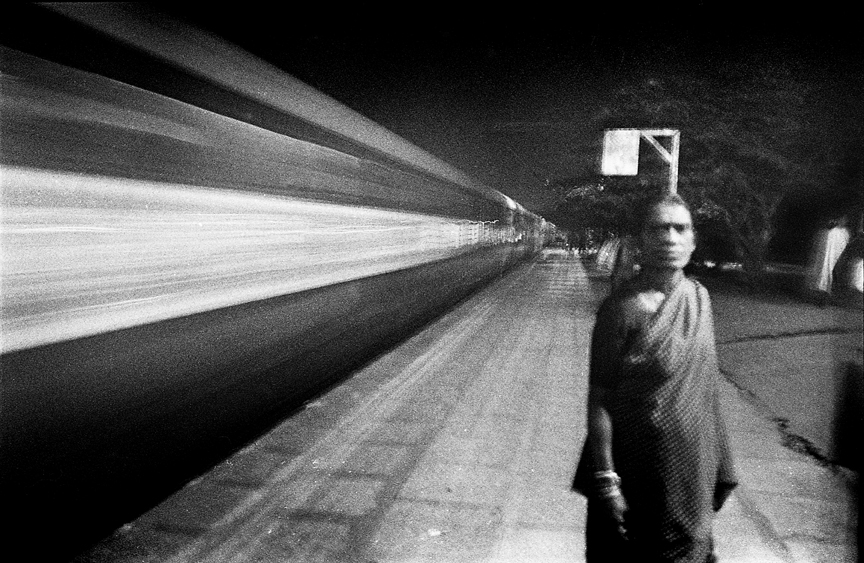

Some of the factories have organised private buses to pick up and drop off their employees. Most are uncomfortably crowded.

Rita, sewing clothes for the neighbourhood, in her house after returning from her days work at the garment factory.

Mallige packs lunch before leaving for her day’s work. She usually starts at 9:00 am and finishes by 5:30 pm. With growing market demands, production increases and many workers are asked to stretch their working hours. Overtime is seldom compensated.

All factories employ heavy security and the entire complex is under strict surveillance. Many of the women are sexually harassed and verbally abused by their male supervisors. Individual complaints are usually ignored and collective voices stifled by the factory management.

Daily purchases of vegetables, fruit and other household goods take place just outside the factory. Many pushcarts and peddlers line the outer perimeter of a garment factory in Bangalore.

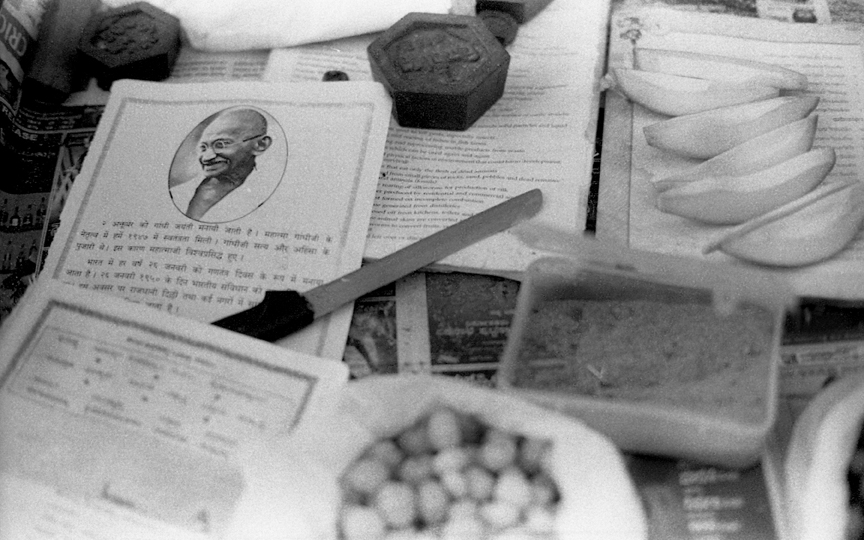

Application forms for scholarships for children of garment workers are distributed by the Garment and Textile Workers’ Union from Bangalore.

A pushcart outside one of the garment factories sells cut fruit.

Mallige returns to her house after work. She lives away from her two children, who stay with her mother in a village a few kilometers from Magadi, near Bangalore.

Gurgaon

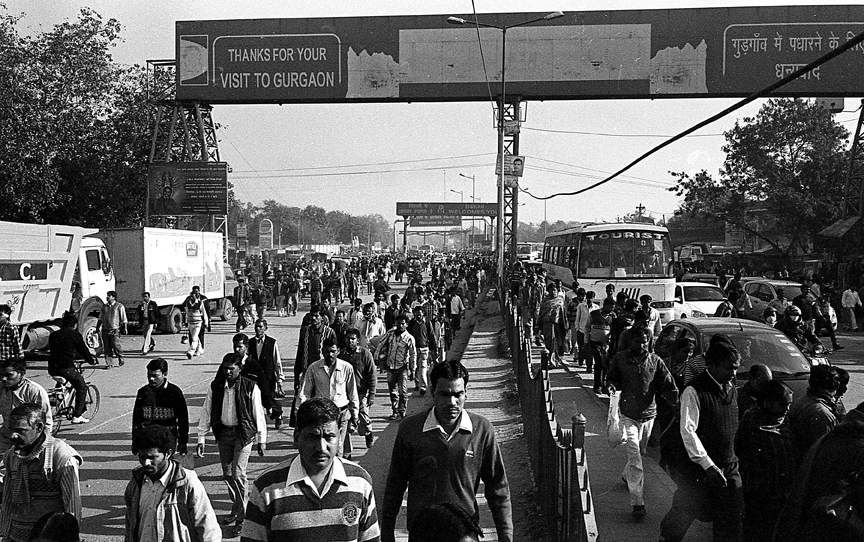

On the outskirts of Gurgaon, which borders with the national capital New Delhi, there is a flurry of people wrestling in a rat race that never ceases. It is Asia’s biggest Special Economic Zone in the making. Thousands of rural migrant workers uprooted by the agrarian crisis stitch and sew for export in over 2,500 manufacturing units. Due to stiff competition from neighbouring countries like Bangladesh, the once sought after tailor is now replaced by operators of machines which are mass producing ready-made garments for the global market.

Here the workforce consists mostly of men – nearly 80 percent and employing over 200,000. The workers are all migrants, majority of them being from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and West Bengal. They are all tucked away in tenements in areas like Kapashera, where hundreds of matchbox-sized, windowless rooms have been constructed to house them and for which they pay 2000 rupees a month. Five to six workers jostle for space in here, but avoid communicating with one another.

I found it to be a rather unnatural human behaviour, not to know of your neighbours or talk to them. It seems that competition is encouraged to run high between workers. The workers themselves have been numbed and desensitized to surroundings with repetitive mechanical actions. Moreover, they are all identified by their room number, not names. The only conversations one hears between them would be that of salaries paid by certain companies. In this way they explore their possibilities with different employers. As a result, they never stay with a particular company for more than six to eight months. At the drop of a hat they find work with a better pay due to great demand for workforce by these export houses.

The working hours here is an excruciating fifteen hours a day or more on most days of the week for which they are never duly paid. I have met workers who have been fired and asked to leave due to banal arguments over the fact that they have had lunch in the same space demarcated solely for the supervisors. Sometimes similar events take an ugly turn: in May of 2013 several workers teamed up and killed their supervisor and his family. These examples talk eloquently of the abuse of power the supervisors exercise, strengthening the casteist hierarchy which, in turn, incites rebellion and violence.

Depending on the weather/season, the worker reacts to these oftentimes adverse climate conditions of the region with either quitting instantly or finding work in another company. The stories of stretching oneself for survival permeate the workers’ colonies here. One feels almost like a tourist, with the groups of relieved or curious workers welcoming you on your visit or thanking you for it.

Workers entering Udyog Vihar, New Delhi.

Garment workers from Kapashera with their children around a temporary polio camp set up in their neighbourhood.

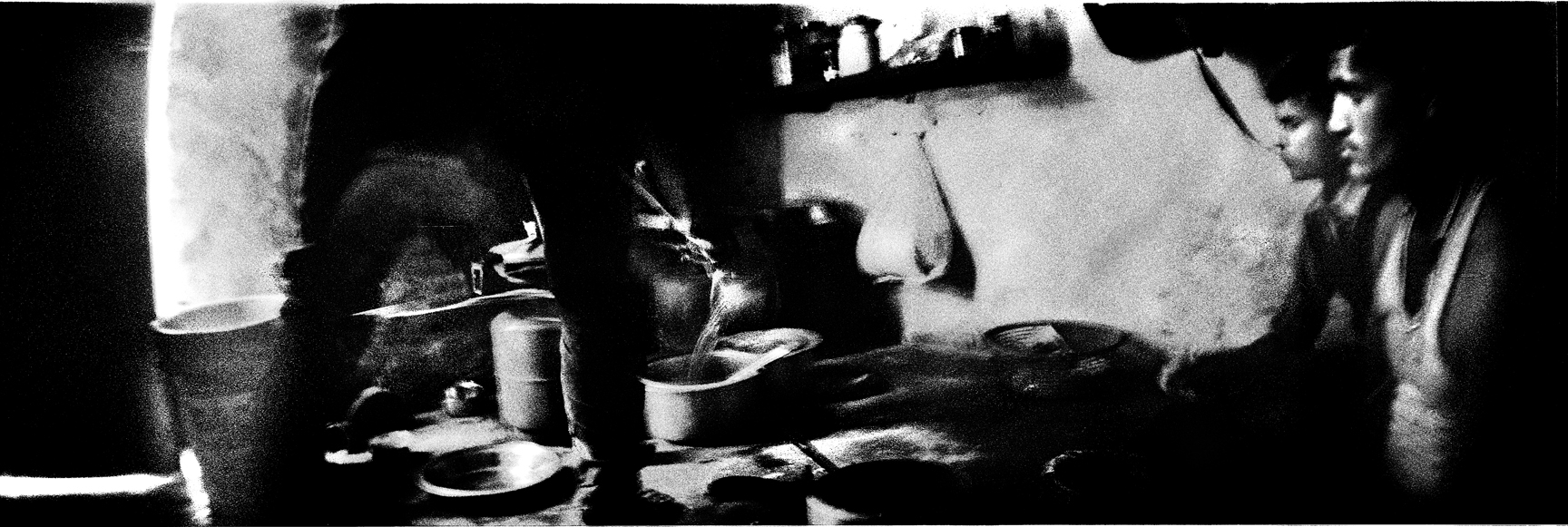

Usually returning home from work late in the night the men cook their food and retire to wake up to another day of stretched work.

Sunday is usually when medical camps from nongovernmental organizations are organized to spread awareness where they also do a basic checkup. Seen here is one such camp spreading awareness on HIV and AIDS.

Kapashera is the border town between New Delhi and Gurgaon. Majority of the garment factories are concentrated in the adjacent Udyog Vihar industrial area.

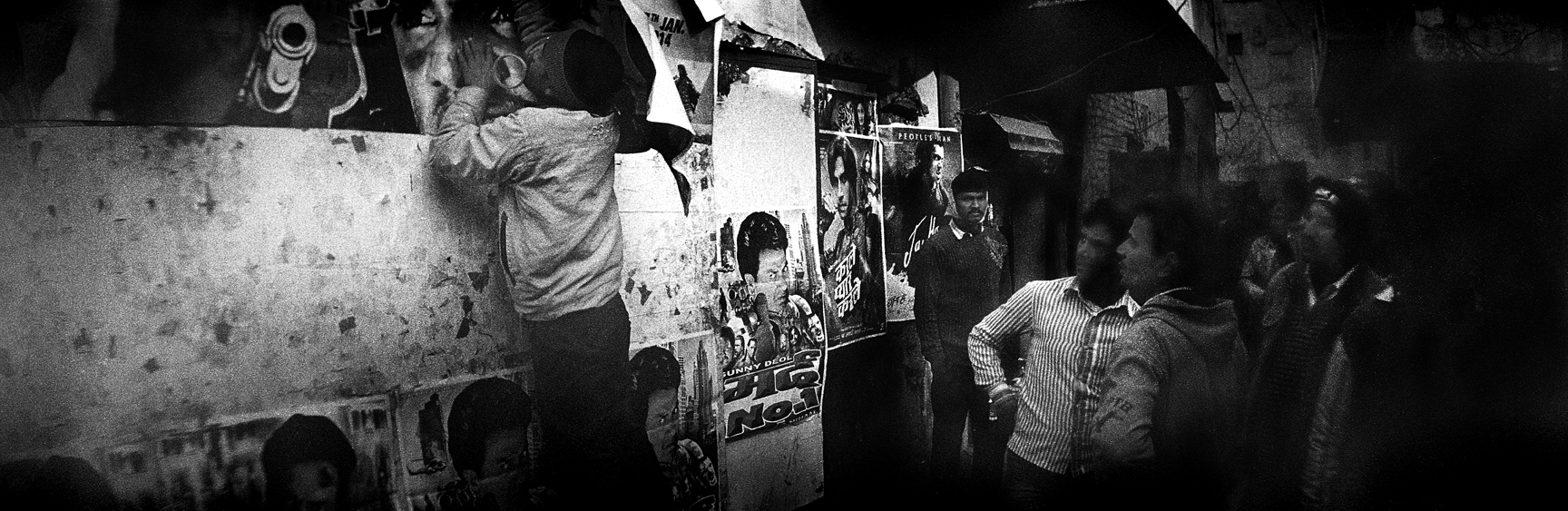

It is only a Sunday or a festival day when the workers get a day off. They spend their day cleaning, shopping, sleeping or preferring to watch a movie at the tent cinema for entertainment.

Construction in Gurgaon is happening round the clock and in every corner.

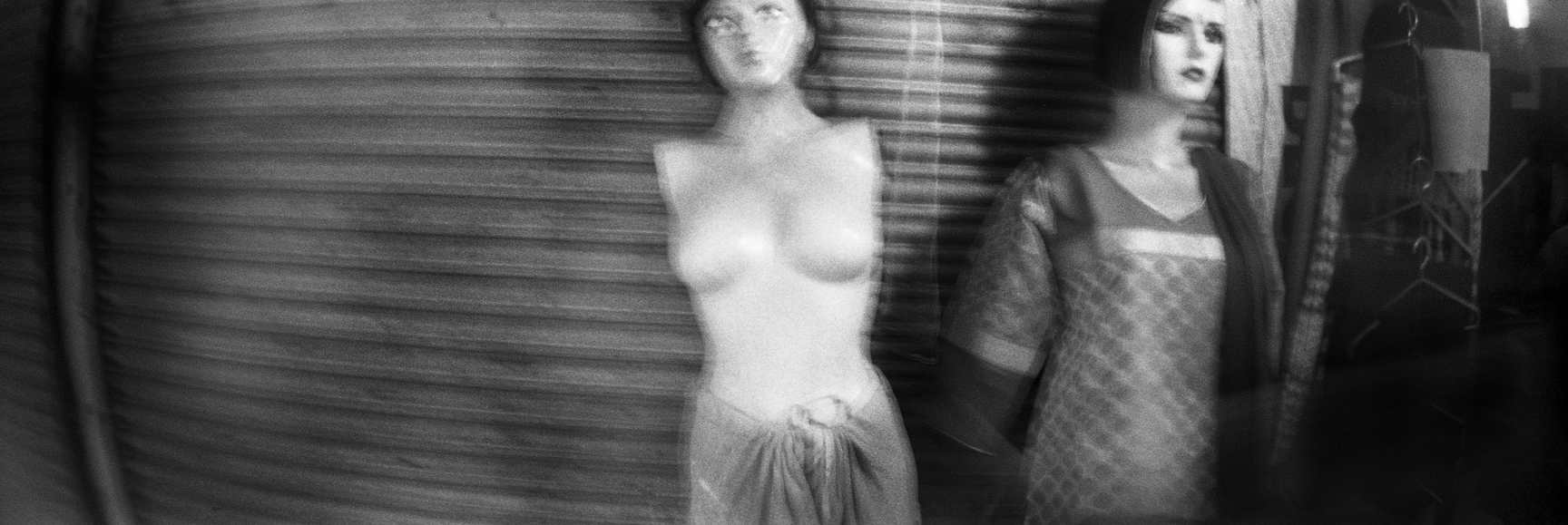

Most the factories in Udyog Vihar manufacture women’s clothing.

A dog behind the tenements of the workers.

Food being prepared.

One of the share toilets inside the compound of a tenement, Kapashera, Haryana.

An early morning scene at one of the tenements where the garment workers stay, Nalli wali Galli, Kapashera.

There are usually four or five men sharing a little room. They share the rent of two thousand rupees for the space.

Workers taking an early morning shower before heading off to work.

Bio:

Rudra Rakshit Sharan is a Bangalore-based photographer.