About 30,000 conservancy workers, also known as sweepers, are employed by the Greater Bombay Municipal Corporation. These workers collect the city’s garbage, sweep the streets, clean the gutters, load and unload garbage trucks and work in the dumping grounds.

All 30,000 of them are Dalits, belonging to the lowest rung of the Indian caste system. They have little or no education. Without exception, all of them despise their work. They are either completely ignored or looked down upon with disgust by the rest of society. They have to work in the midst of filth, with no protective gear, not even access to water for washing off the slime. Most of them are alcoholics and live in poverty, in dismal housing. They are perpetually in debt despite earning what, by Indian standards, is a decent wage of US $152 per month. The workers abuse their wives and children. And when the husbands die (usually at a young age), the despised job passes to the widows. The despair continues.

Few years ago, quite by accident, I descended into the ‘living hell’ – a phrase which quite accurately describes the life of these workers. What I saw shook me to the core of my being. That thousands of men and women were living and working in such dehumanizing conditions filled me with rage and shame.

I wanted to know every thing about these workers. I wanted to know them not just as the ones who cleaned the city’s underbelly, but also as brothers and fellow human beings. I wanted to know their names and what they thought about themselves, their work, their families and their employers. I also wanted to know how they felt about the citizens of Mumbai. And, at a very personal and important level, I wanted to know what they thought about me – one of their own – who had escaped their living hell. This is how I came to bear witness. There was an overwhelming need in me to understand how they could bear their lives, given how they were compelled to work.

Then came a decisive moment when bearing witness and hearing their stories was not enough. I wanted to put myself at their service, using my only talent to make visible these invisible brothers and sisters and to give voice to their ‘never heard before’ stories.

When they gave me, permission to ‘shoot them’, their generosity moved me to tears. I explained in detail what I would have to do in order to tell their stories and told them again and again to reconsider. They said that they did not hope – much less expect – that anything would change for themselves. But if what I was doing could bring about even the smallest change in the lives of their children, they would be eternally grateful to me.

My rage and shame, their faith and trust – these are the forces have impelled over one year to search for dignity and justice, to tell the untold story of conservancy workers.

One of the most important things that I want to do concerns the very role of the photographer himself/herself. I feel strongly that it is not enough for me to bear witness and to document reality. I must also initiate a process of reflection and action. Especially among two key groups.

The first group is the Corporation, which employs the workers. Through my images, I want to dialogue with the corporation in an attempt to work out what it can do to make their working and living conditions more humane and just.

I also want to direct the call for reflection and change towards the public at large. I want the citizens to see the workers and to acknowledge their presence and contribution. I want to create images that drive home the point that without this workforce, life in the city would be rife with ill health, disease and even death.

Only then will I be true to my vision of photography, which is to give a call to action, to urge fellow human beings through my pictures to change the picture.

Each and every one of us creates waste. We do not deny this fact. In Mumbai, we create 7,000 tonnes of waste every day. We know that such huge amounts of garbage can pose a serious health risk and that it could lead to the outbreak of many diseases including cholera, dysentery, typhoid, infective hepatitis and the plague.

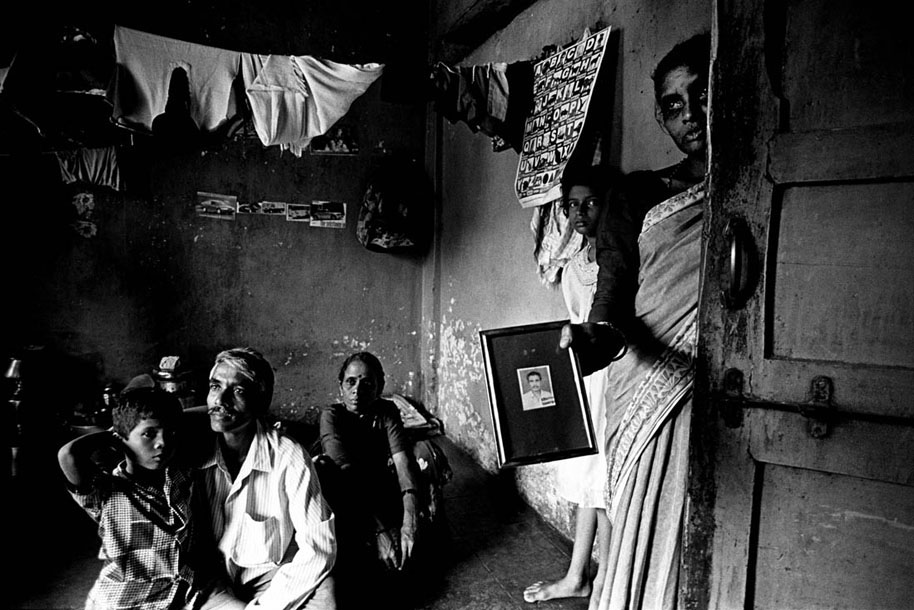

Twenty hard strokes of his heavy, wooden broom are what it takes parmar to sweep one step of the overhead bridge. Sweeping tiny leaves and gathering them in to a small pile requires thirty to forty brisk strokes of the broom. Gathering and pile making has to be done at a quick pace, before the leaves scatter away in the wind. Thirty strokes a pile, ten to twenty piles on a single tree line pavement. How many strokes of a broom does that make in a day?

Workers tirelessly do their job despite the mounting pressure.

The garbage that the workers rake out includes animal carcasses, food remains, steel wires, hospital waste, jagged pieces of wood, pipes, stone, broken glass and blades.

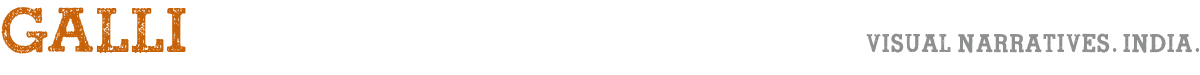

Manek reports to work at 6am. He is always worried that the supervisor will mark him absent and give his duty to a temporary worker. This happens all the time. It is an easy way to make a little money on the side. Manek first sweeps the main road and then around 11am, the supervisor directs him to a house gulli. In this gulli which he has cleaned every day for the last fifteen years, Manek has had boiling rice water, packets of fish shells, beer bottles flung upon him. Once a sanitary napkin landed on him. His co-worker used her broom to wipe the blood off his face. But they did not get out of the gulli. It had to be cleaned.

Clearing garbage is back breaking work. The tools of the trade are primitive. So the body is put to work. Hands pick up the garbage. Shoulders carry it. There are scars where the wooden pole digs into Jadhav’s shoulders. Jadhav does not like to talk about his work. He nods when asked if they hurt.

The western suburbs where these pictures were taken has 65 kilometres of big nallas, 56 kilometres of small nallas and 52 kilometres of box drains. Some of the drainage lines are deep enough to accommodate a double decker bus.

All this is done to make them feel hopeless about themselves.

After an hour or so when the worker comes out, he keeps shivering. This work requires no special skills- just a pair of arms and legs and the courage to descend into hell.

Once inside, there is nothing but darkness. The worker is totally cut off from the world above, anything could happen to him – he could pass out from inhaling some toxic gas, or slip in the slime and lose consciousness, or be carried away in the rush of water and waste.

No human being should have to work in such demeaning and dehumanizing conditions, but the fact is that 30,000 human beings do.

The price they pay – losing a little dignity every day. Bit by bit, till none is left. And they begin to see themselves as garbage, worthy of nothing, not even a little respect.

The trucks which keep coming to the dumping grounds have to be unloaded in the mid-day sun or in the pouring rain.

There are five dumping grounds on the eastern and western edges of the city. The stench is unbearable. The dumping grounds are now filled to capacity. In fact, they are overfilled and this makes the worker’s job even more physically demanding and even more hazardous.

None of the dumping ground sites have as much as small canteen or even a room where the workers can change their clothes or sit during a break.

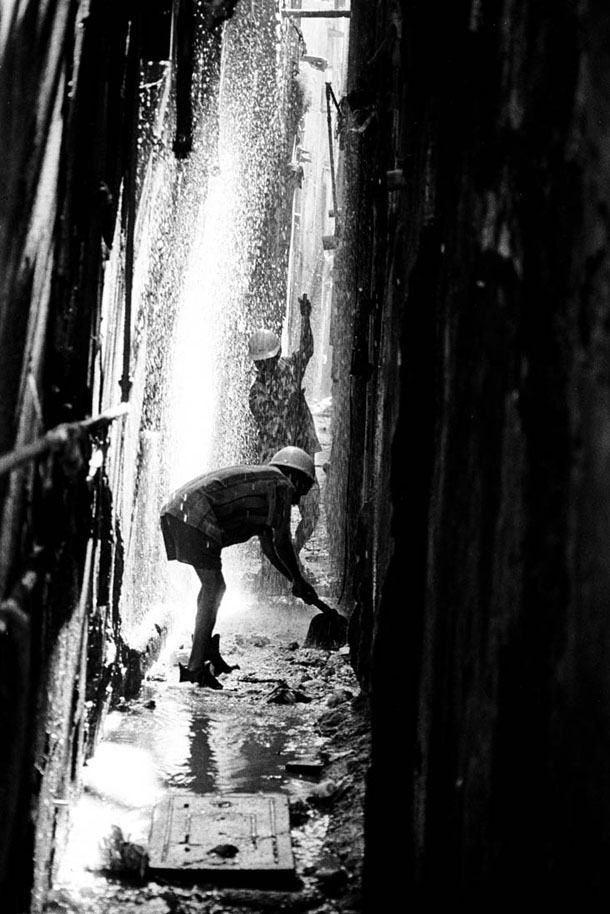

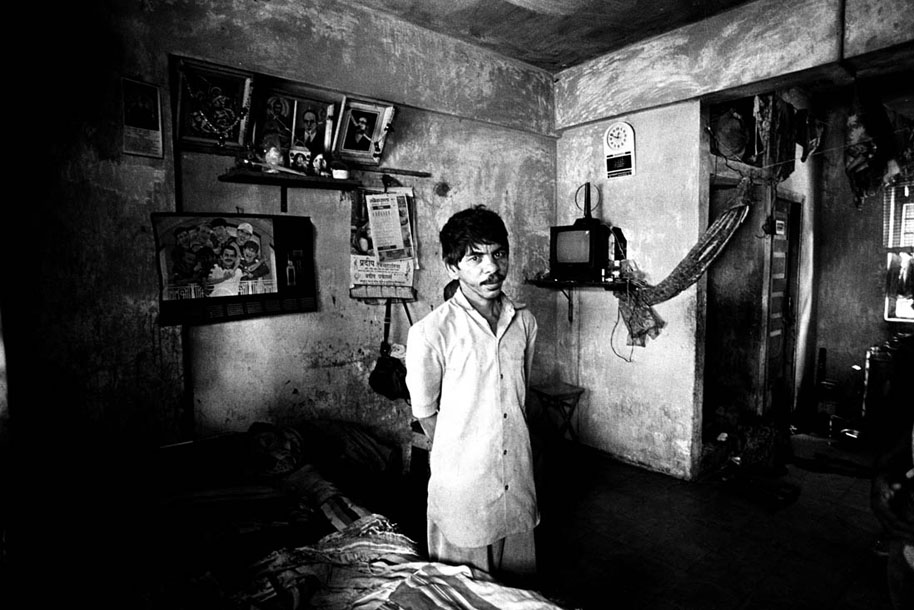

One of the ‘perks’ of the job is getting a kholi (a house). These two families – the one sitting and the other standing – live in the same 10X 12 feet room. This is not an uncommon feature. In many a kholi, a line drawn on the ground demarcated each family’s territory. These two families have not spoken to each other in eight years. The fight is about who the rightful owner of the kholi is – the widow or the brother.

Two to three families, around 20 to 25 people in a single room is a common feature.

Kamble’s wife works as a domestic servant. Sometimes the memsaheb (Madam) gives her food to take home. Home is a portion of the staircase. Kamble’s wife raises three children here.

Hiraman’s wife refused to be photographed as she had nothing to do with any friend of the raakshas (devil) who gives her Rs.150 to run the house for one month. Hiraman kept asking her to shut up. She kept threatening to leave him. Her fury was fierce. It is not likely that Hiraman’s wife will leave. It is more likely that Hiraman who is visibly shrinking will die soon.

Shasi Tambe’s wife returned to her father’s house three years ago when she could not take the beating anymore.

Remarriage is out of question for the widows of these workers as they would lose their jobs as well as their kholis.

By the time the worker reaches home, alcohol has turned him into a tormentor – a crazed demon who abuses and beats his wife and children.

As a citizen and fellow human beings we can change the picture? There are 1.7 million of us in the city of Mumbai. The population has risen steadily over the years. Can the workforce be expanded to cope with the increase in the waste being created? Is it possible for us to reduce the waste we create? Can we look at the workers without mistrust and disdain? Can we acknowledge the contribution they make to our health and survival, at the cost of their own health and survival?

Bio:

Sudharak Olwe has been a photographer for the past 20 years, he has over the years worked with the Times of India, Indian Express, The Pioneer, INDES etc. and has freelanced with Financial Times – London, the European Press Agency(EPA) and has Exhibited his work in Amsterdam, Portugal, Japan, Germany, US, Sweden and Bangladesh.