Since Solzhenitsyn, the idea of the cancer ward has always been a sterile place, where those who have this dreaded disease are segregated from society. But in the city in which I live, there is a cancer ward open to the sky.

When I first visited Lady Jerbai Wadia Road, a small back lane in central Bombay, there was nothing to distinguish this little community of 15 to 20 families from all the millions of residents of this city who live on the pavements. The difference lay in the details: the child wearing a medical mask and playing with a cat, the way a woman smiling at me from under a tree had covered her thinning hair with a jaunty head scarf; and a plastic bag hanging on a railing, a plastic bag marked “CT Scan”. These are the patients on the pavement, the spillover from the Tata Memorial Hospital, Asia’s largest cancer treatment facility.

It was easy to see this as yet another manifestation of the failures of a third world nation, the lack of medical infrastructure. But over the next few months I found the story behind the story. There are secular and religious institutions that will offer these patients a bed but often they are crowded, even claustrophobic, as one patient put it. Sometimes, they are far away and a patient may be too weak to make the trek to and from the home. And anyway, when 43,000 new patients arrive every year, some are going to end up on the street, especially since 70 per cent are treated free of charge.

The patients who lie down on the street are not resigned to their fate; they are waging a determined battle against it. They do not want to die. They want to live and they will do what it takes to get better again, even if it means recuperating from the savageries of radiation therapy in the dust thrown up by passing cars and huddling under plastic sheets when the torrential sub-equatorial monsoons wash the city.

I learnt that a community grows among these cancer patients and their family members who have made the journey from various corners of India’s rural heartlands to the Tata Memorial Hospital.

But these impressive numbers also contribute to the one thing that brings all these people together: an infinity of waiting. They wait endlessly, for an appointment with the doctor, for a diagnosis or a result of a test, for their turn at an operation or at a chemotherapy session, and finally, the wait to get better.

The plight of the pavement patients has triggered a number of philanthropic responses. Some provide free nutritious meals or distribute tarpaulins and blankets for protection against the weather. And in a city where fights over water are not uncommon, the inmates of a nearby chawl (one room tenements with common toilets and bathrooms) are magnanimous enough to allow the families to fill water from the communal taps. When your water supply is measured in hours per day, this is genuine sharing.

Some may die on the street. Many more will survive. They will go back to the back-breaking work of scratching a living from the soil and return each year for an annual check-up. But while they are here, they are a community that shares an enemy: cancer. They battle the rain and the flies. They learn to live with the cacophony of the city’s traffic and the way pedestrians may intrude upon their space at will. They bathe. They eat. They find time to play and laugh and gossip and grumble. They look out for each other and guard each other’s belongings. They forge a community and they refuse to admit defeat.

As a manifestation of the transcendence of the human spirit, the community of temporary residents of Lady Jerbai Wadia Road is hard to beat.

Babarao Pandurang Gawli. District – Thane, Maharashtra

For days on end I saw this man sitting motionless, staring blankly at the busy road in front of him. He resembled a skeleton draped in an oversized shirt and a pair of loose navy blue shorts. His only movement was when he picked up the plastic container to spit or to adjust the tube emerging from his throat and in to his nose.

Babanrao, 60, has cancer of the throat. He was a labourer, a daily wage earner, and had a habit of drinking and that too cheap locally brewed hooch. Smoking beedis just added to his problems and today he can barely speak.

Babanrao Gawli and Babybai, 55, his wife, who is staying with him here on the pavement outside the Tata Memorial Hospital, India’s premier cancer treatment facility, have their home at Virar, one of the northernmost suburbs of Mumbai that can be reached by an hour and fourty-five minute long journey by train.

Siadulari. District – Banda, Uttar Pradesh

Poverty is just one of the reasons why some of the patients and their families decide to stay on this stretch of pavement outside the hospital. For many who stay here it is hard even to afford the Rs.50 (approximately 1US$) daily rental at one of the many ashrams and homes around the city for cancer patients. The need for accommodation is so acute that the Tata hospital itself set up the Ernst Borges Home to provide free accommodation to at least a few of them.

Many patients, however, complain of the claustrophobic environs of some of these places. Bishwanath, one such patient, from Uttar Pradesh, said he was scared that he would catch more infections at these places. Others like Shyamal Chowdhuri, from West Bengal, prefer to “sleep under the trees” as he simply prefers the open skies.

Siadulari, from Banda district of Uttar Pradesh, (pictured here), and her family decided to reside here because they felt the nausea caused by her radiation therapy would make it difficult for her to travel to the hospital in the buses that ferry patients to and fro from these homes for their appointments. Girjashankar, her husband points out, “For the women patients the biggest problem is using the latrine”.

Mohammed Israil Mansuri. District – Satna, Madhya Pradesh

The Mansuri brothers, from Satna district in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, had an appointment with the doctors later in the afternoon that day when I was first introduced to them. Israil, 18, seemed despondent as he said, “My operation was supposed to happen on the second of June but that was the day for voting here in Bombay and so it got postponed…It’s not my fault, I told them, and they told us to either wait till the next date or take my file and get lost,” said Ismail, his brother. For scores of patients, the wait can be unbearable. Ismail, 21, the elder of the two brothers remembers how the family went into shock when they first heard the news about the cancer. “These are all fancy diseases…we call them raja-maharajaon ki bimiriyan… At home everybody wondered how this fellow could get cancer?” he said with a little laugh trying to humour his brother.

A complication while treating a fracture after a motorbike accident led to the discovery of Israil’s cancer. “First the local doctors thought the constant pain was due to something like arthritis…and then when the problem persisted some suggested go to this hakim and that vaid…you know how it is in the village,” Ismail trailed off. Finally they met another local doctor, a bone specialist, who told them the leg would need to be amputated if the treatment were to be done in their hometown. “But he also said, that if the leg had to be saved then that could only be possible here in Mumbai,” he adds. And that’s how the two brothers eventually made their way to the big city.

Over the next few weeks, Ismail, who had put his studies on hold often talked anxiously about his studies. Home, where their father runs a tobacco business, seemed far away. In Satna, they always traveled on their motorbikes. “Look at us now;” says Ismail, “we have to live here on the pavement like beggars.”

Israil has finally undergone his surgery successfully and when this picture was made mentioned that he had two more check-up sessions pending before he would leave for home.

Jeevan Jyot Trust

Patients who arrive at the gates of the hospital from distant towns and villages often talked about the first shock of experiencing the big city. One such person, about ten years back, had approached Harakhchand Savla for guidance about treatment at the Tata Memorial Hospital. In a hurry to get to his workplace, Savla gave some vague advice and brushed aside the request and walked away. But Savla felt guilty for months on end. “I could have helped that man. It wouldn’t have cost me anything,” says the ex-restaurateur. Today, he runs the Jeevan Jyot Trust providing free medicines and meals to nearly 250 needy patients and their families each day. His hole-in-the wall office in the lane adjoining the hospital sees a steady flow of patients who arrive with all sorts of queries – how to organize funds for treatment, places to stay or simply to make sense of the maze of the hospital’s system. Savla and his team patiently sit through it all providing moral support if other requests are hard to meet. “This is my prayaschit (expiation) for the wrong I did by not helping that man,” he says.

It is 7.15 in the morning and at one end of the road, people have started to queue up for the distribution of breakfast. They however start assembling from about an hour earlier leaving plastic bags, bottles, sometimes a bowl or a lunch pail or even their slippers as a symbolic booking of their place in the queue.

After a short prayer, the food distribution begins.

Like the Jeevan Jyot Trust, this free distribution of food referred to as Khichdi Ghar is a philanthropic undertaking of the Shri Vardhaman Jagriti Yuvak Mandal – a Jain trust many of whose members are small traders and shopkeepers from the neighbourhood. Breakfast usually consists of khichdi (a thick paste of rice and lentils), milk, rotis, and seasonal fruit.

Lady Jerbai Wadia Road attracts its fair share of philanthropes. In a city notorious for water shortages, the residents of a nearby tenement have provided free access for the patients to the community tap in their premises. Virendra Kumar Gupta, a patient and his wife maintain that the real problem on the pavement is not food, but water. “One has to admit…whatever the troubles one may have here…the filth, the mosquitoes, the noise…no one will ever sleep hungry,” they said.

Keshav Sontake. District – Nanded, Maharashtra

Thirteen year-old Keshav Sontake has lost his appetite. It’s been this way for some days now, says his mother Chandrakala who is coaxing him to at least have a biscuit. In the background, Baburao, Keshav’s father, a farm labourer, is tying his dhoti (a waist-cloth), getting ready to join the breakfast queue. As his wife hands him a tumbler for the milk, they get into a little argument. Baburao is very tentative about standing in the queue as he was refused rations the previous day. “They will not give us the food if they don’t see the patient,” he tells me. “But that’s impossible. There must be others, attendants like you, who are standing in place of the patients,” I try to explain. Baburao’s not convinced and quite embarrassed about the possibility of being sent back empty handed once again. “Patients can’t always be expected to wait in the queue,” I added trying to reason with him. In the end his wife goes and joins the end of the queue. She returns with a tumbler of milk, some khichdi and two oranges.

A week later when I return I am informed that the Sontakes have gone back home to Nanded (in southern Maharashtra) or so their neighbours on the pavement have me believe. They inform me that the biopsy report had “ruled out cancer”. They also said that after the fracture the boy had suffered, the wound hadn’t healed properly and there was some sort of internal growth leading to a swelling as a result of which the family suspected that it was cancerous. They have now been asked to return home where the correct treatment could happen in a fraction of the cost.

Rajaram and Ramanand Kumar. District – Madhubani, Bihar

7 year old Rajaram gets into a mock battle with his elder brother Ramanand one morning as his parents have gone off to pick up the free rations that are distributed to patients and their families. Like their parents it is not uncommon for others too to leave behind their children when they have to go off on errands. People on the pavement routinely look after children and patients of their neighbours’ families.

As time passes and the pavement becomes like a home, albeit a temporary one, new friends are made and pets adopted.

A lady prays in the afternoon as she sits surrounded by her family’s belongings waiting for the others to return from an appointment with the doctors across the road. I had hoped to speak with her but I never saw her again during my later visits.

Babanrao and Babybai Gawli. District – Thane, Maharashtra

Babanrao, who I used to see each day, sitting in the same position with a blank stare, had for the past week started giving me a nod and a faint smile as a sign of recognition.

“Even the liquids that he takes, he throws up now…he has no strength left,” said Babybai, 55, his wife, as she warms some water to give him a bath. “He’s been complaining of stiffness and body aches,” she adds. ‘It’s bound to happen, no…? All he does is sit here in this one position… Often he dozes off…” she complained.

The elderly couple lives at Virar, one of the northernmost suburbs of Mumbai that can be reached by a two-hour long journey by the suburban trains. “Earlier we used to go back each weekend and then come back on a Monday…but then slowly his weakness (from a month-long radiation treatment) meant that it was difficult for him to cross the foot over bridge to board the train…and you know how crowded the trains are,” she says while giving him a massage and at the same time keeping an eye on the stove on which she is heating the water.

Babybai, who earned about a 100 rupees (approximately 2 US$) a day by hiring out mats to tourists who visited the beach near her home, has no idea how long she can hold on.

As the weeks passed I sometimes saw Babanrao walking about with the help of a stick. And then one day they were gone…and in their place were the belongings of another patient.

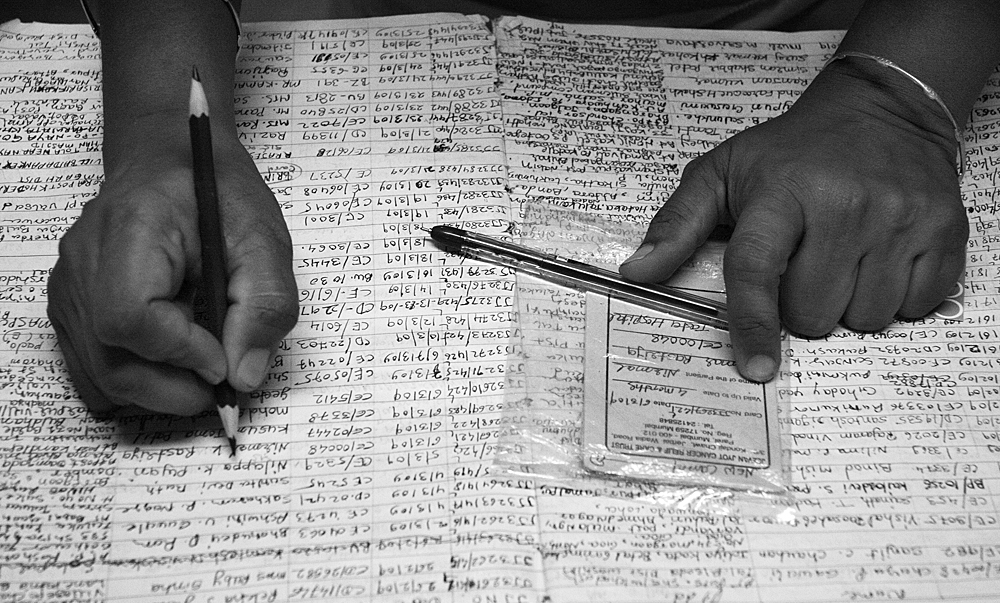

During the mid-afternoons, one doesn’t see too many of the patients here on the pavement since many may have gone across the road to keep their appointments with their doctors. What are left behind are their belongings – clothes, utensils, medicines and documents. “It is all safe here…nothing is ever stolen. We too keep a watch over the belongings of those staying around us,” Manoj Shah, who has been staying on this pavement for more than a year now, had mentioned to me once.

The monsoons were to hit the city a few months after I started this project. Kunwarpal, who was sitting waiting for his brother and sister-in-law to return from inside the hospital said one day, “My greatest worry now is about what will happen during the rains…we have to ensure that our reports and documents are safe and dry.”

Bio:

Chirodeep Chaudhuri’s photographs appear in a number of influential anthologies, his work has been exhibited in India and abroad. He is the editor of photography of ‘Mumbai Now’, the contemporary section of the much admired Bombay Then, Mumbai Now(2009). His new book “A Village in Bengal: Photographs and an Essay” has just been published by Pan Macmillan.